Qvevris – The ancient heartbeat of Georgian Wines

Qvevris, Georgian Wine and other new and useful knowledge

Qvevris are old, practical, magical and contemporary. They are the ancient vessels used for 10,000 years or more in the making of wine; pure, Natural Wine.

I am part of the Second International Qvevri Wine Symposium, and travelling through Georgia with a terrifically engineered group of wine makers, wine writers and one tourism-type, trying to figure out how to design some tourism programs that will incorporate the rather extraordinary Georgian industry.

Firstly, however, a few words about Georgia.

I am not talking about Atlanta; I refer to the Republic of Georgia, tucked away nicely at the eastern end of the Black Sea, due south of some of the more eccentric regions of the Russian Federation and due north of Turkey and Armenia. It is a peaceful and stunning beautiful country of some 4.5 million souls leading their land to a rather new and interesting prosperity. The country has had more than its share of problems with invaders; since the 4th century, and probably before.

The political issues of the Caucasus make the politics of teenage girls seem simple. From invasion to invasion, political and economic alliances, disputes of all manner of shapes and sizes, wine was being made, consumed and keeping the Georgians, an extremely convivial race, content.

And this is where the Qvevri comes in. They are large (300 – 3,500 litre) earthenware vessels that are coated inside with beeswax and buried in the ground. The region is the home of wine making, a craft that has like so many other artisanal occupations edged ever closer to the chemistry laboratory over the years; but not in Georgia.

Wine is still made in the traditional manner by many producers (some producing up to 5,000 bottles per year and almost every family. It is said that in the basement of some urban apartment blocks there are qvevris available for the tenants. The recipe is straightforward; take the Georgian grapes (and believe me, when one finds that there are in excess of 500 varieties that grow in this country, most with names that defeat most non-Georgian speakers, this choice is not easy), crush them pouring the juice into the qvevri. Add stems to taste, and seal the top of the pot; return after a few weeks or months to remove the skins and wood, or not as the wine maker chooses. After sufficient time, take the lid off the vessel, draw off the liquid, taste, smile and invite as many friends as you can think of, the local singers and prepare a feast.

The Georgian “supra” is a meal to behold; medieval quantities of food piled on itself in an explosion of colour and taste, groaning tables, considerably laughter, polyphonic singing and not an eye on Facebook.

Evenings get late, jokes become more ribald, and perhaps emotions overflow, but usually this is only in the continuous expressions of love, friendship and the other values so encouraged by the consumption of the wine. There are worse ways to spend an evening.

And in the morning, despite the over-refreshment of the night before, heads are memorably clear to head off and sample more of these extraordinary products.

Georgia’s isolation, geographically and geopolitically has had one major benefit; the country in the early 21st century is truly organic, and at a time that the world is demanding more natural products. If the government is able to embrace this, and brand Georgia as a “Natural” country, it has a special and valuable place in the world economy.

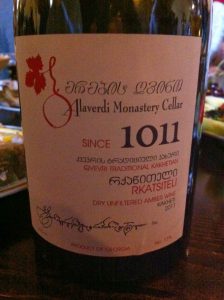

However, the future is far in the distance; today it is off to the Alaverdi monastery to see their wine production, and have the monks cook us lunch.